Vienna’s electorate gap – district by district

20.9.2015 by ramon bauer

The population of Vienna has been growing since the late 1980s. Population growth even accelerated after the turn of the millennium, driven by increasing international immigration. The new arrivals are usually ineligible for voting, as only Austrian nationals are enfranchised, and as a consequence both the share and the number of people of voting age who are not eligible to vote has risen.

Two years ago, I discussed the deepening democratic deficit related to the increasing number of (disenfranchised) foreign nationals in Vienna in a Metropop post. Just in time for the upcoming 2015 Vienna election (to be held on 11 October), I take up the topic of Vienna’s shrinking electorate once more, and in more detail.

The shrinking electorate of Vienna (part II)

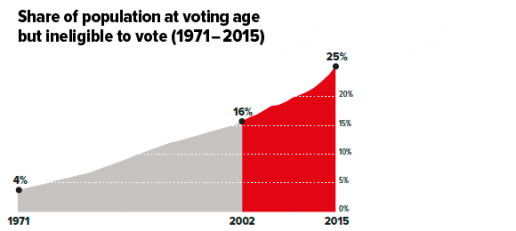

Back in 1971, virtually every inhabitant of Vienna was Austrian by nationality national, hence 96% of the people at voting age were eligible to vote. Since then, the share of foreign nationals at voting age has gone up and so has the share of people at voting age who are not eligible to vote: from 4% in 1971 to 16% in 2002 and up to 25% in 2015. This means that one out of four people at voting age will be unable to participate in the 2015 Vienna elections.

The period 2002 to 2015 is especially interesting with respect to Vienna’s widening electorate gap, i.e. the number or share of people old enough to vote who remain ineligible to do so. First, population growth driven by an increasing influx of international immigrants has accelerated since 2002, making Vienna one of the fastest growing capital cities in Europe. Second, tighter naturalisation requirements became effective in 2006, which makes it more difficult for foreign nationals to acquire Austrian citizenship and thus the right to vote. Third, the lowering of the voting age from 18 years to 16 years added 27,948 additional persons to the electorate in 2007. Finally, a solid register-based time series of annual population data since 2002 (by Statistics Austria) makes it possible to dig deeper into the topic.

The period 2002 to 2015 is especially interesting with respect to Vienna’s widening electorate gap, i.e. the number or share of people old enough to vote who remain ineligible to do so. First, population growth driven by an increasing influx of international immigrants has accelerated since 2002, making Vienna one of the fastest growing capital cities in Europe. Second, tighter naturalisation requirements became effective in 2006, which makes it more difficult for foreign nationals to acquire Austrian citizenship and thus the right to vote. Third, the lowering of the voting age from 18 years to 16 years added 27,948 additional persons to the electorate in 2007. Finally, a solid register-based time series of annual population data since 2002 (by Statistics Austria) makes it possible to dig deeper into the topic.

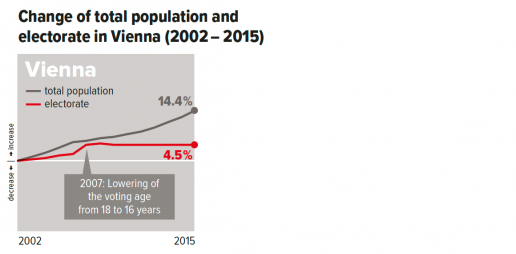

Vienna’s electorate gap is increasing because the growth of the electorate is not keeping pace with population growth. The city’s total population grew by 14.4% between 2002 and 2015 (from less than 1.6 million to 1.8 million) while the electorate has increased by just 4.5% (or less than twenty-four thousand persons). The chart above clearly shows that at least half of the electorate’s net gains since 2002 can be attributed to the lowering of the voting age in 2007. The data map below illustrates how the electorate has changed between 2002 and 2015 (in %) in relation to the total population, district by district.

Vienna’s electorate gap is increasing because the growth of the electorate is not keeping pace with population growth. The city’s total population grew by 14.4% between 2002 and 2015 (from less than 1.6 million to 1.8 million) while the electorate has increased by just 4.5% (or less than twenty-four thousand persons). The chart above clearly shows that at least half of the electorate’s net gains since 2002 can be attributed to the lowering of the voting age in 2007. The data map below illustrates how the electorate has changed between 2002 and 2015 (in %) in relation to the total population, district by district.

See also our Vienna electorate gap infographic (elaborated together with Tina Frank and Michael Holzapfel) as well as the interactive data map (coded by Clemens Schrammel).

See also our Vienna electorate gap infographic (elaborated together with Tina Frank and Michael Holzapfel) as well as the interactive data map (coded by Clemens Schrammel).

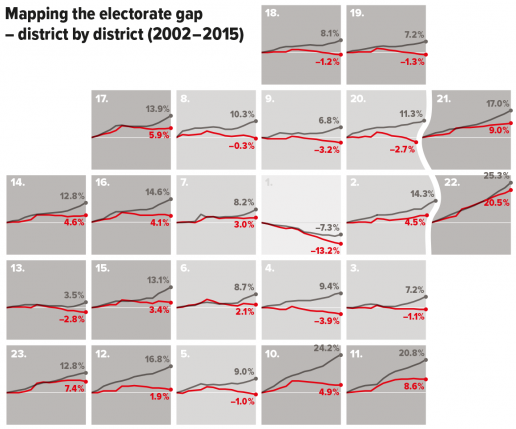

All districts of Vienna gained population between 2002 and 2015 except for the 1st district. The combination of population growth and a stagnating or decreasing electorate (as observed since 2002) affected the city’s twenty-three districts differently. In general, the gap between total population and eligible voters has widened everywhere across Vienna. However, some districts with a strong population growth had only small electorate gains (such as the 10th, 11th, and 12th districts). Other districts experienced an average population growth but a decline of the electorate, which also resulted in a widening gap (such as the 4th, 9th , 18th, and 20th districts). But there are also districts with both a strong population growth since 2002 and a moderate increase in the electorate gap, with the best example being the 22nd district.

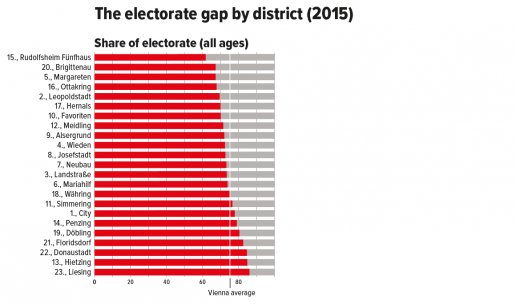

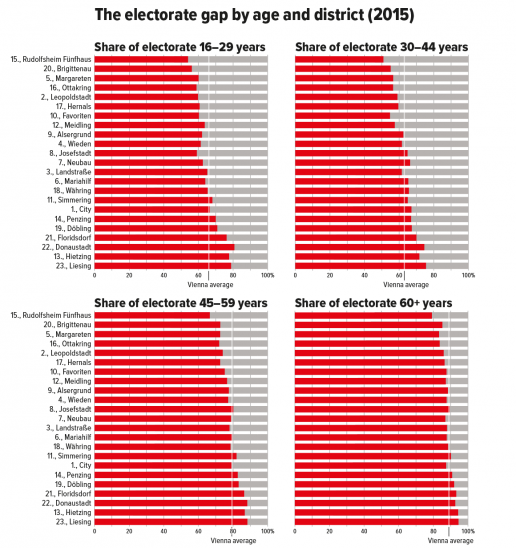

Note: Red columns show the share of people who are eligible to vote, grey columns indicate the share of those who are ineligible to vote (in%). Click image to enlarge.

Note: Red columns show the share of people who are eligible to vote, grey columns indicate the share of those who are ineligible to vote (in%). Click image to enlarge.

As of the beginning of 2015, Vienna’s electorate gap was widest in the 15th district, where less than 62% of the voting-age population is eligible to vote. Several other districts feature electoral representation below 70%. Smaller electoral gaps with respect to the citywide average are prevalent mainly in outer districts (such as the 13th, 19th, 21th, 22nd, and 23rd district) – check out our infographic for additional maps.

Vienna’s electorate gap varies significantly by age. In general, the share of eligible voters is lower in younger age groups (below 45 years) and higher in older age groups. This is mainly because the vast majority of international immigrants are young adults. Immigrants who remain in Vienna for some years often eventually acquire Austrian citizenship, and hence become part of the electorate.

Note: Red columns show the share of people who are eligible to vote, grey columns indicate the share of those who are ineligible to vote (in%). Click image to enlarge.

Note: Red columns show the share of people who are eligible to vote, grey columns indicate the share of those who are ineligible to vote (in%). Click image to enlarge.

Differentiating by broad age groups, only two-thirds of 16 to 29 year-olds are eligible for voting. The share of young voters differs between Vienna’s districts, ranging from 54% (15th district) to 81% (21st district). The city’s electorate gap is widest among those between 30 and 44 years of age. Only 63% of the population at young working age is eligible to vote. Their share is lowest in the 15th district, where half of young adults are excluded from participating in citywide or national elections. Those at prime working age between 45 and 59 years have a smaller average electorate gap. The citywide average of eligible voters in this age group is 80%, which ranges from 66% (15th district) to 88% (22nd and 23rd district). The electorate gap amongst residents age 60+ is the smallest in Vienna, with 90% eligible to vote. Although Vienna’s seniors represent only about 22% of the total population, they account for 31% of Vienna’s 2015 electorate.

Who is left to vote?

Vienna has a growing democratic deficit. Already, 25% of the voting-age population is excluded from participating in citywide and national elections. On top of that, not every eligible voter is actually going to the polls. In Vienna, the average voter turnout at national and federal-state elections since 2002 is 68.8%. Assuming this average turnout for the coming 2015 Vienna elections, only 784.000 persons, or around 43% of Vienna’s entire population, will elect the next city council.

A widening electorate gap due to an increase in foreign nationals is a predominately urban phenomenon. Cities are hubs of international migration. Vienna, for example, represents 21% of the Austrian population and more than 40% of its share of foreign nationals. The situation in the Austrian capital city exemplifies an increasing democratic deficit that is prevalent in many other cities with strong population growth driven by international migration.

So, how to narrow an electorate gap? In countries with rather strict naturalisation requirements such as Austria, a less restrictive legislation would generate more eligible voters (a forthcoming Metropop post will deal with this topic). Another option is to link the eligibility for voting to the length of residency rather than to the nationality. Such a paradigm shift would ensure that almost every citizen would be enabled to participate in the political process.

References:

- Population data: Statistics Austria

- Voter turnout data: City of Vienna

See also:

- Vienna electorate – A collection of Metropop contributions to the topic of Vienna’s shrinking electorate.

- Vienna’s electorate gap infographic – Available for download as PDF poster.

- Vienna’s electorate gap data map – Interactive data map of Vienna (district by district).

- London Squared Map – Innovative data map and inspiration for the Metropop Vienna electorate gap data map.

No comments. Would you like to leave a comment here?